Nutrition research is really hard

I’ve mentioned many times how notoriously flawed nutrition research is, and hopefully instilled in you the sense that you should remain skeptical about what hear in the media and online. And its not because the scientists are not brilliant (trust me, they are)…

For this post I want to talk briefly about the types of nutrition research, which will help you, as the consumer, to sort through many of the bogus headlines you see online about what you should or should not eat.

(Hint: most of them are to be ignored)

There are two major types of medical research: observational and interventional

Observational studies: Researchers observe and analyze outcomes without manipulating variables. They do not assign exposures (e.g., diets, treatments); they simply study what people are already doing.

Types of observational studies:

Cross-sectional: measures exposure and outcome at a single point in time. For example, a survey of current eating habits and cholesterol levels.

Cohort (Prospective or Retrospective): Follows people over time based on exposure. For example, following vegetarians versus omnivores over 10 years to track incidence of heart disease.

Case-control: Compares people with a condition (cases) to those without (controls), looking backward at exposures. For example, comparing past diets of people with colon cancer to those without.

Observational studies can only establish correlation, NOT CAUSATION.

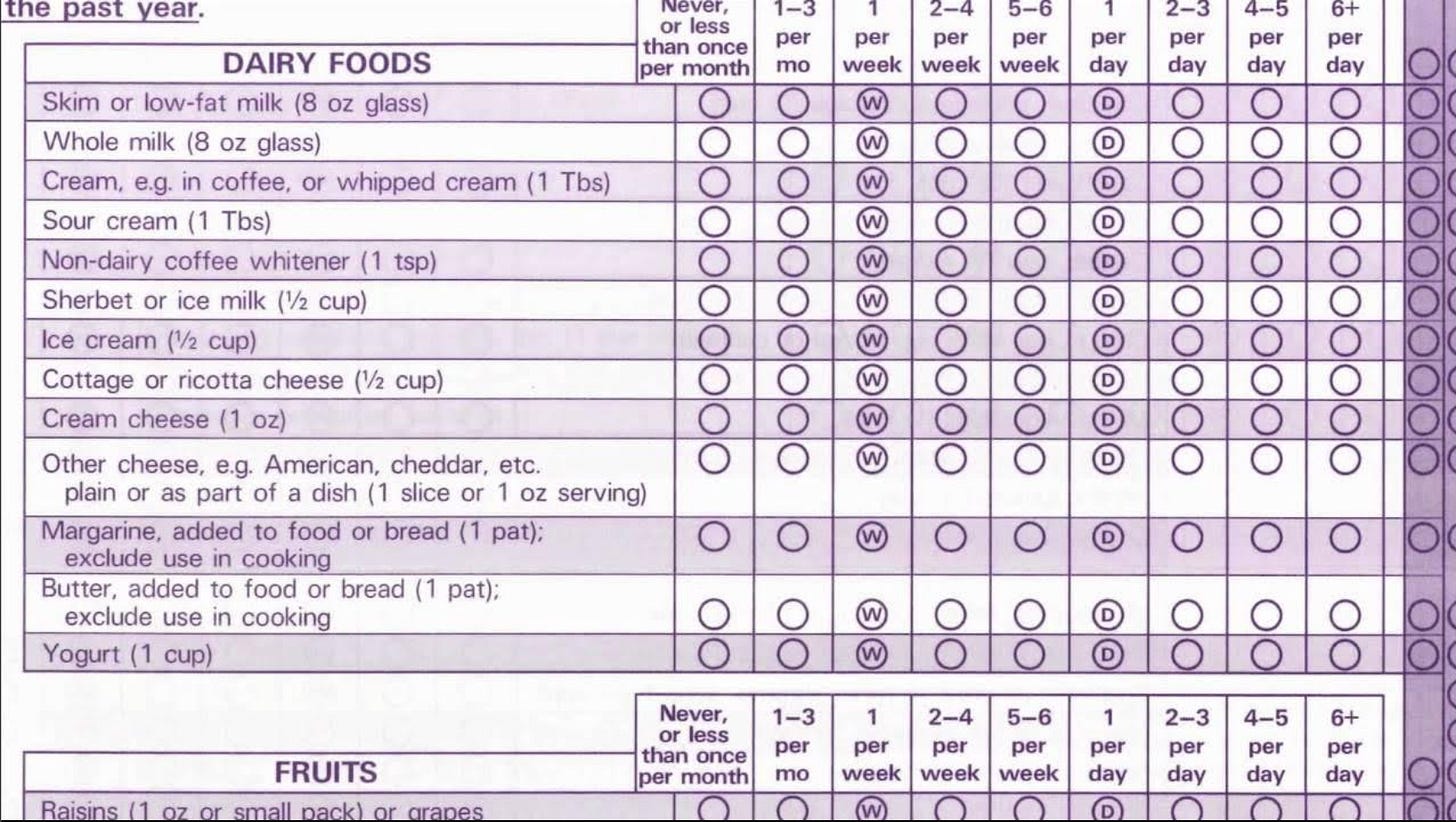

Most nutrition research is observational — i.e. watching eating patterns over time, collecting data using food frequency questionnaires (which have MANY pitfalls — try remembering everything you’ve had to eat in the past 2 weeks…), and seeing what health outcomes different dietary groups experience.

Accurately measuring dietary intake is inherently difficult and many studies rely on self reported data which is subject to many errors and biases (4). For example…

A great example of an observational trial is the Nurses’ Health Study (cohort), which has tracked thousands of nurses diets and health outcomes over decades.

This observational study found the following: women consuming ≥2 servings/day of sugar-sweetened beverages had a 35% higher risk of cardiovascular disease compared to those consuming <1 serving/month, even after adjusting for other dietary and lifestyle factors (1).

Main message: SSB consumption in women is associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease.

But we cannot say (at least not yet) that SSBs CAUSE heart disease. Maybe there is another factor that is actually mediating that relationship, such as living in a food dessert or a nutrient deficiency from an overall poor dietary pattern, and SSB intake is simply happening alongside this.

Note: This is not what I personally think is happening — we have a lot of evidence that SSBs have negative health effects (see meta analysis and review here (5)) — but just a thought experiment to show that observational studies cannot establish causation.

Confounding variables are a major issue with observational research, especially nutrition research (4). You cannot separate socioeconomic, behavioral, and environmental factors from the dietary patterns of an individual over an observational study period.

Many studies try to makeup for this pitfall by utilizing statistical analyses to “control” for factors such as BMI, physical activity, socioeconomic status, etc. — but it is impossible for an observational study to fully control for the complexity of these variables.

There are certain qualities however that can suggest validity of a correlation: 1) the study adjusted for confounding variables (as above + more) 2) a dose-response relationship 3) the finding is replicated in additional studies 4) biological plausibility (i.e. the relationship has a biological mechanism that makes sense).

Anytime you hear something saying a dietary pattern / food is “associated with”, “linked to”, “correlated with”, “predictive of”, “tied to”, or “higher/lower risk of” — think observational study.

And remember that correlation does NOT equal causation. Does that mean the association is wrong? No.

It just means we need more research to say 100% yes.

These correlations should be used to generate hypotheses to be tested in interventional studies.

Now, let’s move on to the gold standard… 🥇

Interventional (Experimental) studies: Researchers assign an exposure or treatment (i.e. one diet versus another) to participants to examine its effect on an outcome. These are actively controlled experiments.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): Participants are randomly assigned to intervention or control group.

For example (made up): Researchers randomly assign 200 adults with prediabetes to either a Mediterranean diet group or a low-fat diet group. Meals are provided, and participants are followed for 12 months to assess changes in blood glucose and insulin sensitivity.

Non-randomized trails: Intervention assigned, but not randomized. More susceptible to bias.

For example (also made up): Researchers recruit 200 adults who have chosen to follow either a Mediterranean diet or a low-fat diet on their own. They follow them over 12 months and compare changes in blood glucose.

Some nutrition research cannot ethically be performed through randomized controlled trials because extensive observational evidence has already demonstrated harm—making it unethical to randomly assign participants to consume potentially dangerous diets.

For example, given the well-established association between sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) intake and increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, it would be unethical to require a group of participants to consume high amounts of SSBs over time solely for the sake of comparison.

Nutrition research is notoriously hard to carry out through RCTs…

…even though RCTs are the gold standard for establishing causality. Theres a reason we don’t have as much data for nutritional interventions through experimental studies. And it’s not for lack of trying.

Here’s a few reasons why:

Diets are complex — not a single variable

You cannot easily isolate a single nutrient without changing others

For example, comparing a low fat diet vs a low carb diet requires changing both the % carbs and the % of fats that someone is eating — was it the change in carbs or fat that made the difference?

Food is eaten in patterns, not in isolation

For example, replacing saturated fat with refined carbohydrates has different effects than replacing them with unsaturated fats.

Diets are hard to control over time

Long term adherence is challenging — patients instructed to consume a certain diet may not follow directions, forget, or misreport what they are actually eating. Personal habits, food access, social events, preferences and more all impact compliance.

For example, imagine being asked to eat the Mediterranean diet for 5 years and never deviate — its unrealistic.

Blinding is nearly impossible

People can see what they are eating. Both researcher expectations and/or bias from participants can influence outcomes.

Outcomes take a long time to develop

Chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer don’t develop over weeks — they take years or even decades. Obtaining results from a nutrition RCT requires very long and very expensive studies.

Individual variability

Different individuals respond better to different diets due to many factors — genetics, microbiome, activity level, sleep, stress, social circumstances, etc. One person may thrive on a plant based diet while another feels better on a lower carbohydrate diet — this is nearly impossible to control for.

Overall, conducting RCTs in nutrition is logistically challenging, which is why a lot of nutritional science tries to make do with combining evidence from a variety of study designs (both observational and interventional).

To make this even worse, news headlines cherry pick and simplify information into tidbits that misrepresent an already imperfect science. No wonder everyone, including myself, is so confused.

Here’s a little summary for ya…

And one last thing…

What are metabolic wards and how are they helpful?

Some nutrition studies utilize something called a “metabolic ward” to study specific nutritional interventions.

A metabolic ward is a highly controlled inpatient research facility designed to precisely monitor and regulate all aspects of a study participants diet, physical activity and environment during short term nutrition studies.

This allows for rigorous control over dietary exposure and minimizing of external confounding variables that cloud data from observational studies.

No need to rely on food questionnaires — researchers know exactly what an individual eats, how much, the precise macro/micro nutrients and much more.

While they are incredibly resource-intensive and often limited in duration and sample size, they are still considered the gold standard for metabolic research in human nutrition (2,3).

Next, I want to explore more in depth a study that utilizes a metabolic ward and randomized controlled design to assess the effect of an ultra-processed food diet vs an unprocessed diet on food intake and weight gain.

Hint: it’s not looking great for the ultra-processed food stans…

Stay tuned 😊

References 😘

Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19211821/

Human metabolic chambers reveal a coordinated metabolic-physiologic response to nutrition, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39576013/

Challenges in conducting clinical nutrition research, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28605476/

Perspective: Limiting Dependence on Nonrandomized Studies and Improving Randomized Trials in Human Nutrition Research: Why and How, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30032218/

Intake of Sugar-Sweetened and Low-Calorie Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32696948/